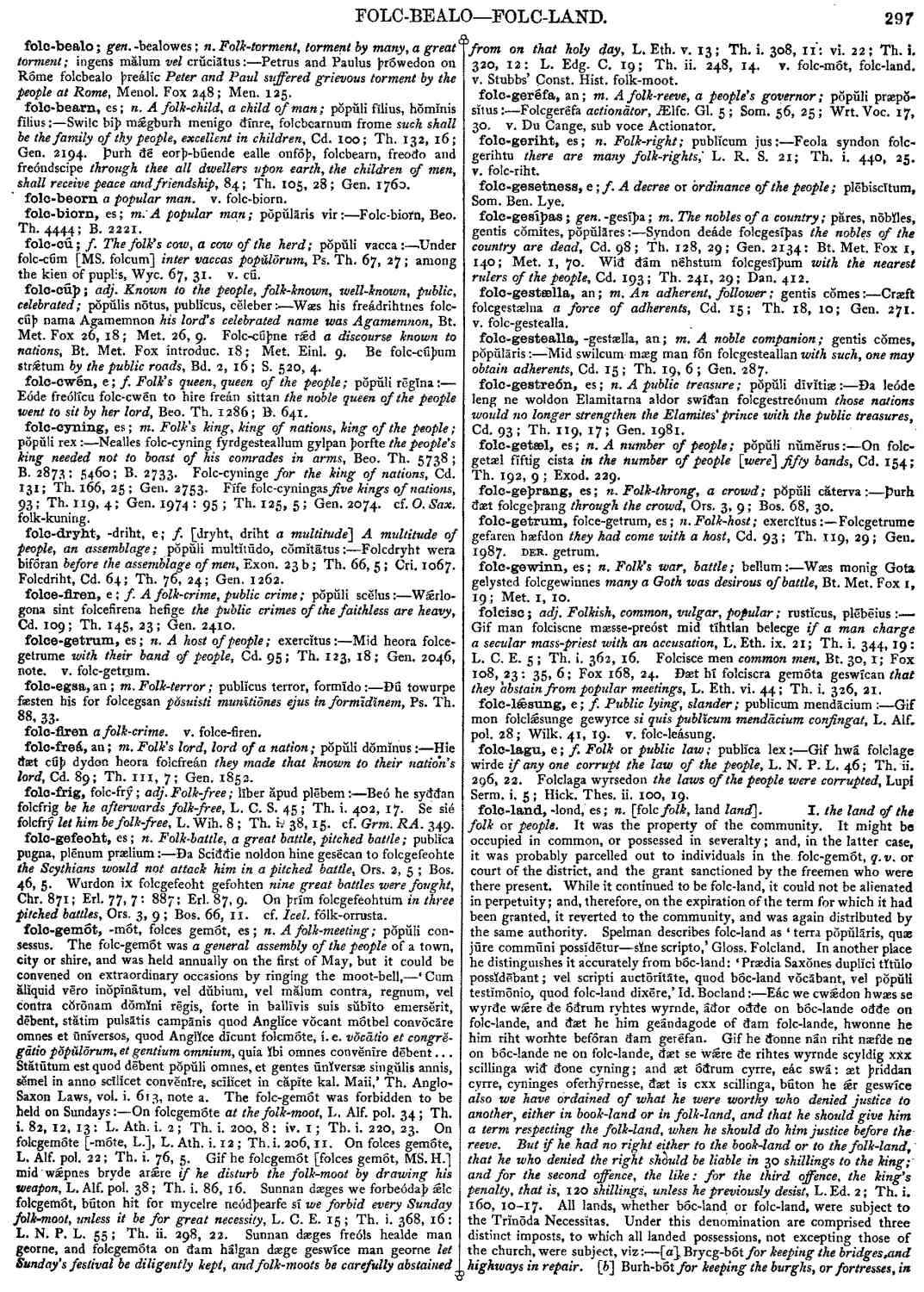

folc-land

- noun [ neuter ]

-

Eác we cwǽdon hwæs se wyrðe wǽre ðe óðrum ryhtes wyrnde, áðor oððe on bóc-lande oððe on folc-lande, and ðæt he him geándagode of ðam folc-lande, hwonne he him riht worhte befóran ðam geréfan. Gif he ðonne nán riht næfde ne on bóc-lande ne on folc-lande, ðæt se wǽre ðe rihtes wyrnde scyldig xxx scillinga wið ðone cyning; and æt óðrum cyrre, eác swá: æt þriddan cyrre, cyninges oferhýrnesse, ðæt is cxx scillinga, búton he ǽr geswíce

also we have ordained of what he were worthy who denied justice to another, either in book-land or in folk-land, and that he should give him a term respecting the folk-land, when he should do him justice before the reeve. But if he had no right either to the book-land or to the folk-land, that he who denied the right should be liable in 30 shillings to the king; and for the second offence, the like: for the third offence, the king's penalty, that is, 120 shillings, unless he previously desist,

- L. Ed. 2 ;

- Th. i. 160, 10-17.

-

Gif hwá Burh-bóte, oððe Brycg-bóte, oððe Fyrd-fare forsitte; gebáte mid hund-twelftigum scillinga ðam cyningce on Engla lage, and on Dena lage, swá hit ǽr stód

if any one neglect Burh-bót, or Brycg-bót, or Fyrd-fare; let him make amends with one hundred and twenty shillings to the king by English law, and by Danish law, as it formerly stood,

- L. C. S. 66 ;

- Th. i. 410, 8-10.

-

Þegenes lagu is, ðæt he sý his bóc-rihtes wyrðe, and ðæt he þreó þinc of his lande dó, fyrd-færeld, and burh-bóte, and brycg-geweorc [MS. bryc-]

thane's law is, that he be worthy to make his will, and that he perform three things for his land, military service, repairs of fortresses, and of bridges,

- L. R. S. 1 ;

- Th. i. 432, 1-3.

- Anglo-Saxon Dict., App. ii. 2.

- Somner's Gavelkind, 88, 211 ;

- Hickes, Pref. xxxii ;

- Diss. Epist. 29, 54, 55, 59 ;

- Madox, Formul. 395

- Lambarde, Kent, 540 ;

- Hickes, Diss. Epist. 54 ;

- Gale, i. 457 ;

- Lye's Append. ii. 1, 5 ;

- Heming. 40

- Hickes, Diss. Epist. 62.

- Smith's Bede, 305-312

- Text. Roffens. 72, edit. Hearne ;

- Kemble, Cod. Dipl. No. cxi.

- L. Th. ii. Glossary, Folc-land: Sandys' Gavel. 97.

Bosworth, Joseph. “folc-land.” In An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary Online, edited by Thomas Northcote Toller, Christ Sean, and Ondřej Tichy. Prague: Faculty of Arts, Charles University, 2014. https://bosworthtoller.com/11106.

Checked: 1